HONORING LANDSCAPE INTERCONNECTIVITY

THE MOAB TO MOJAVE CONSERVATION CORRIDOR

By Kevin Berend

GREETINGS FROM GRAND STAIRCASE ESCALANTE NATIONAL MONUMENT, your neighbor a few hundred miles to the northeast. Did you know that our monuments are connected through a new landscape corridor?

Water, earth and air do not adhere to lines drawn on a map. Plants and animals do not respect conceptual boundaries, and they often require much larger landscapes than humans allow. As climate change continues to alter the Earth’s ecosystems and the behavior of wildlife, planning for connectivity through the creation of landscape corridors can preserve the pathways that plants, animals and insects need as they travel northward in latitude and upward in elevation to reach more desirable temperatures. To stay healthy, landscapes require interconnection.

In my day job, I work as the Conservation Programs Manager for Grand Staircase Escalante Partners, and I spend my free time enjoying the beautiful landscape of Southern Utah and its surroundings, so I’m excited to see that the need for connectivity has led to the rise of landscape-scale conservation. Ecological corridors recognize the extensive natural interconnectivity of our nation’s ecosystems, and prioritize large-scale connectivity across jurisdictional boundaries such as national parks and monuments.

Landscape-scale conservation includes working to reduce and mitigate pollution, create safe passage for wildlife across roads and fences, and ensure healthy riparian (streamside) habitats for fish, birds, and insect pollinators. Such efforts are already underway in North America, including the well-known Yellowstone to Yukon corridor in the Rocky Mountains and the Algonquin to Adirondacks corridor in the northeast.

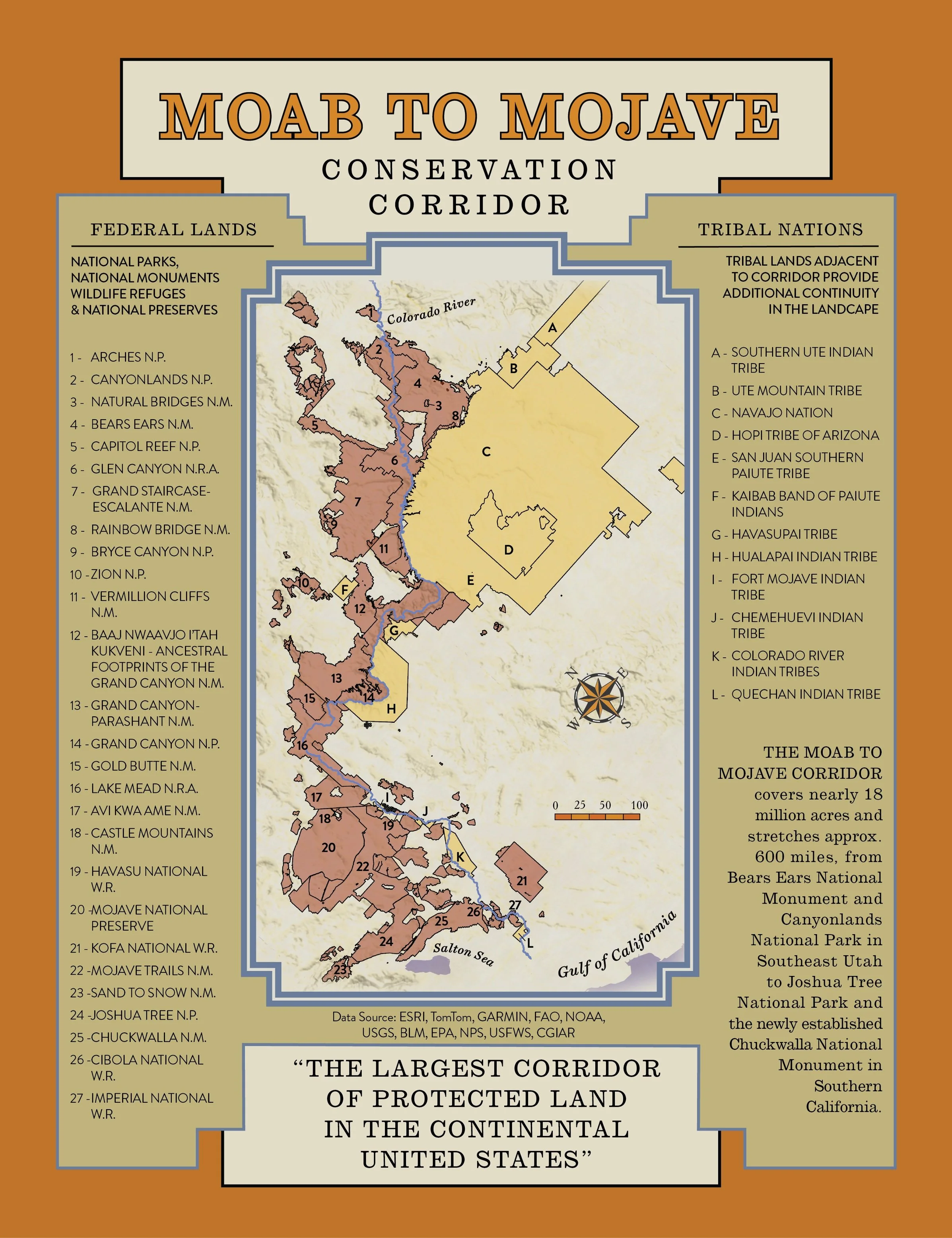

In January, as one of his last actions before leaving office, President Joe Biden signed an executive order establishing the Moab to Mojave Conservation Corridor (M2M), which spotlights landscape connectivity in the Southwest. The Moab to Mojave Corridor covers nearly 18 million acres and stretches approximately 600 miles, from Bears Ears National Monument and Canyonlands National Park in Southeast Utah to Joshua Tree National Park and the newly established Chuckwalla National Monument in Southern California. The corridor links five national parks with 12 national monuments, The Mojave National Preserve and Glen Canyon and Lake Mead National Recreation Areas. According to the National Parks Conservation Association, it is the “largest corridor of protected land in the continental United States.”

The M2M corridor already includes some of the most heavily visited tourist destinations in the country, but due to rapid population growth, the Colorado River and its sub-basins are experiencing some of the heaviest demand of any natural resources in the nation. As pressures for commercial and industrial development mount across this arid landscape, the connectivity of the greater Colorado River will be crucial to maintaining both biological integrity and human habitability.

A photo of the Escalante River within Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument. Photograph by Kevin Berend.

For example, in the Southwest, big game such as mule deer, pronghorn, elk, and desert bighorn sheep undertake daily and seasonal migrations, navigating urban sprawl and frequently crossing treacherous roads and highways. Riparian ecosystems harbor the region’s greatest biodiversity, and are crucial habitat for birds, fish, and rare plants. Riverscapes, therefore, demand attention as a whole to keep them healthy, rather than seeing them as a series of disconnected parts. By offering a framework for land managers, tribal nations, non-profit partners and community groups to work holistically on creative solutions to the challenges of habitat connectivity, M2M can strengthen ecological links between public land units, and act as a crucial bridge to the future.

The Moab to Mojave corridor will also help preserve tribal sovereignty for the many Native American nations that call the Colorado River home. Much as nature does not adhere to arbitrary borders, the history and stories of native peoples weave a complex fabric that permeates ancestral territories across this entire landscape. For tribal nations who have been repeatedly stripped of land and rights—and for whom history is literally written into land itself—M2M provides an additional basis for the protection of cultural heritage sites within the context of the natural landscape.

Finally, the Moab to Mojave corridor seeks to promote wise commercial and industrial development, including housing, renewable energy projects, and oil & gas production. Since recreation is a major economic driver across the corridor’s natural landscape, unobstructed viewsheds are one of its prized assets. Landscape-scale connectivity allows for preservation of the natural aesthetic experience that local communities and tourists alike hold dear. This does not mean blocking all development; rather, the recognition of the larger landscape corridor can be an additional tool to help bring communities into the decisions about the lands that affect the shape of their lives and livelihoods.

The goal of landscape-scale conservation is to find balance in how we engage with the land for short-term and long-term benefits that aid both humans and the environment. Designation of national monuments, such as Baaj-Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni and Avi Kwa Ame, both established recently by President Biden, focus on protecting land that is historically, culturally and ecologically important to local communities and the nation. Designation of the Moab to Mojave corridor does not preclude existing land uses such as grazing, hunting, OHV use, or rockhounding. These issues are discussed extensively with local communities as part of the designation and management plan process, and reflect the wants and needs of each area’s residents.

It remains to be seen how the Moab to Mojave corridor will be implemented on the ground, but it does begin to orient federal policy toward a broader, more inclusive view of what public lands are for and how best to steward them. This landscape-scale concept may also help galvanize support across its geography among nonprofit partners and the general public, allowing greater cooperation on shared conservation initiatives and goals in the future.

I was lucky enough to visit Avi Kwa Ame last November, when I camped among Joshua trees at the Wee Thump Wilderness and hiked through a rugged, narrow canyon. Though the views were different from Utah, I was reminded of the timeless continuity of water, rock, and life across this vast desert. I invite you to visit Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and experience another part of this boundaryless landscape for yourself!